Is the Word Marijuana Racist?

And Other Questions of Nomenclature

The R Word

I am often approached by journalists or podcasters with questions about the origins of the word “marijuana” and its place in the history of cannabis in the United States. Usually their curiosity has been sparked by the widespread notion that the word “marijuana” is racist. As noted in an earlier post, the racism argument has its origins in Jack Herer’s conspiracy tome: Hemp and the Marijuana Conspiracy: The Emperor Wears No Clothes. Herer argued that prior to the 1920s or 30s (he’s not specific), hardly anyone in the United States had heard the word “marijuana,” and simply knew cannabis as “hemp” or “cannabis,” or perhaps “Indian hemp” or “hashish.” But then, he claimed, an aggrieved William Randolph Hearst decided to pound the term into the American lexicon in an effort to make the drug sound more foreign and thereby facilitate its demonization.

One obvious problem with this theory was the idea that a new foreign word was required to exoticize cannabis. After all, since the nineteenth century drug cannabis had commonly been referred to by the quintessentially orientalist term “hashish,” or the similarly foreign sounding Indian hemp. Why, we might ask, was “marihuana” supposed to be so much worse? But the biggest problem was that Herer’s theory was based on precisely zero evidence of any intentional act by Hearst or anyone else to begin using this apparently Mexican word. [1] Nonetheless, Herer’s racism thesis has been extraordinarily influential as evidenced by recent efforts in various states to strike the word “marijuana” from legislation and other official documents.

While the theory has no real basis, it does reflect the general sense in much of the literature that I’ve already alluded to, namely that something strange must have occurred with cannabis in the early twentieth century for this drug to have been prohibited. Herer’s interpretation is just the most conspiratorial and least evidence-based of the more widespread idea that, before the 1920s, cannabis was a relatively uncontroversial substance. While Adam Rathge has demonstrated that this was hardly the case, the literature has yet to systematically interrogate the evolving nomenclature of cannabis in the early twentieth century.

What then can our data tell us about these questions?

Methodology and Findings

In order to pursue this and related questions, we took note of the nomenclature used for intoxicant cannabis in each of the 1,225 articles we examined for the period 1910-1919. For each article, with a few exceptions, we listed up to three terms used.[2] In the data these show up as “Term” “Term II” and “Term III.” These shouldn’t be read as a strict hierarchy of importance as that was sometimes too subjective to be a stated goal, though I think that in most cases it worked out that way.

Consider our first visualization which provides just a basic count of the words most frequently used for intoxicant cannabis in the Chronicling America corpus between 1910 and the end of 1919.

Here we see that by far the most prominent term for drug cannabis during this decade was “hashish,” a word with overwhelming orientalist connotations (more on that below). Hashish (this includes the alternate spelling “hasheesh”) appeared as a primary term for drug cannabis in 652 articles, more than twice as many as any other word, with “marihuana” (including alternate spellings) coming in second at 275 articles. These were followed by “Cannabis indica” (161) and “Indian Hemp” (89).

Here are is another visualization of the same data:

And another:

And these numbers were clearly not simply an artifact of our method of determining primary and secondary terms in a particular story, for the vast majority of these stories included only one term for cannabis. For example, of the 652 articles that we marked as having “hashish” as the primary term, 445 had no second or third term at all. Of the 273 stories with “marihuana” as the primary nomenclature, 210 did not include a second or third term, and so forth. This is even clearer when we look at a list of our secondary terms alone [Note that there were a few other outlying terms that I did not include so as to make the visualization more legible. These included: “Larkspur,” (3); “Chang” (2); “Keef” (2); “Narwana” (1); “Indian Cannabis” (1); “Mota” (1); “Dogbane” (1)]:

863 out of 1,225 stories had no second term at all.

Terms III follows a similar pattern:

93% of the stories had no tertiary term, but still hashish was among the most prominent of these.

Finally, we can look at how often Terms I and II showed up in concert with each other:

As well as Terms I, II, and III:

Ok, so what does this data tell us so far?

First, intoxicant cannabis was not a frequent feature of the press during this period. Our final story count of 1,225 articles out of roughly 450,000 newspaper issues demonstrates that quite clearly, though it’s perhaps more useful to compare with the frequency that other intoxicants show up when searched in chronicling America. Now, for this exercise we will actually use the current version of Chronicling America because we did not do this comparison back in 2019 when we finished collecting our data and thus can’t do it now. But the object is just to get a rough sense of how common these words were in the press in comparison to each other and we have no reason to think that those proportions will be significantly different now than they were back in 2019. It’s not a perfect exercise, but it’s enough to give us a basic idea.

For comparison’s sake I searched marihuana (584), mariguana (16), marijuana (19), hashish (513) hasheesh (439); Indian hemp (293) cannabis (299); and cannabis indica (115) for a total of 2,278 hits in the cannabis category. This is of course almost twice as many articles as in our final count for this project using the 2019 corpus, but keep in mind that the issue count in the corpus has increased considerably (about 26%, from 453,839 to 574,456), many articles will come up twice because they include multiple cannabis terms (and thus would only have been counted by us once), and these basic searches always include a number of false hits and articles that would not be counted in the final tally (see note 2). In any case, for comparison’s sake, while the various terms for cannabis turned up 2,278 hits, a search for “alcohol” turned up 266,511, “morphine” 77,735, and “cocaine” 22,921. Obviously, intoxicant cannabis was not a major element of the press in the United States in the early twentieth century. Though this isn’t totally unique. Even in Mexico, where intoxicant cannabis use had been commented on for decades, references to the drug in the press were dwarfed by those to alcohol and morphine. Below is a pie chart from my book comparing newspaper references to marijuana and other known intoxicants for the period 1880-1922. It’s not a perfect comparison as the dates are different and so is some of the terminology, but it clearly shows that marijuana references were not very common in Mexico either:

Nonetheless, the relative dearth of references to intoxicant cannabis in the American press reinforces a seeming paradox that I’ve noted elsewhere (pp. 18-19), namely, given that intoxicant cannabis had been easily acquired at pharmacies since the mid-nineteenth century in the United States, and that its reputation as an intoxicant was relatively well known (as demonstrated by Adam Rathge), why hadn’t its use become more common by the early twentieth century? Was it that the typical edible doses used in the nineteenth and early twentieth century had a tendency to produce unpleasant overdoses in users and thus recreational use only became more widespread when the marijuana cigarette did? Or was it, as many sources of the early twentieth century suggested, that cannabis was growing in popularity due to “substitution,” that is, it being used to substitute for the various other substances that were being banned at the time? Or was it something else? We still don’t know.

In any case, while intoxicant cannabis was relatively unusual in the press, the most common word used with respect to it was overwhelmingly “hashish” (or “hasheesh”). Second was “marihuana” (or much less commonly, “mariguana” or “marijuana”). However, geography was also key here. If we look at the data on our interactive map, this becomes quite obvious. The map has the added advantage that you can manipulate it on your own by checking and unchecking the boxes below it (read this guide first).

First consider “hashish” versus “marihuana” references. Hashish stories were relatively evenly spread out with a few hotspots among the major cites of the East Coast:

Click on the map to view in Tableau where you can manipulate the variables yourself (user guide here)

Marihuana stories were, on the other hand, overwhelmingly located in Texas and Arizona.

Click on the map to view in Tableau where you can manipulate the variables yourself (user guide here)

And the marihuana data is actually even more specific than this, something that becomes clear if we compare the cities where marihuana stories were published versus the cities where hashish stories were published. Hashish stories were once again relatively evenly distributed with hotspots in New York City and Washington, D.C.

Click on the map to view in Tableau where you can manipulate the variables yourself (user guide here)

Marihuana stories, on the other hand, were especially concentrated in just three cities: El Paso, San Antonio, and Phoenix.

Click on the map to view in Tableau where you can manipulate the variables yourself (user guide here)

But if we remove the Spanish-language press from the map, San Antonio, which had a major Spanish-language newspaper, almost disappears.

Click on the map to view in Tableau where you can manipulate the variables yourself (user guide here)

In short, press coverage of marihuana in El Paso and Phoenix was relatively intense in comparison to anywhere else in the country. In my SHAD piece (pp. 25-28) I note a similar geographic concentration in Texas, with El Paso and San Antonio reporting considerable marijuana sales, but other cities in the region, including those with a significant Mexican presence, reporting very little or none at all. While I speculate there on why El Paso and San Antonio might have been outliers, to my knowledge Phoenix has not previously been recognized as a specific hotspot for marihuana. The data is particularly interesting if we look at the references to “marihuana” in these two states chronologically. Here’s Arizona:

And Texas:

And here is the City level data with Spanish language separated out. First Arizona cities:

Texas cities:

In the case of Phoenix there’s clearly an uptick after 1916 (the city passed a marijuana ordinance in 1917). In San Antonio there is a clear upward trend around the same time. El Paso, which passed a marihuana ordinance in 1915, shows a more erratic pattern. But, again, the Phoenix story has not been much, if ever, commented on in the literature. If you are looking for a research topic, this is certainly an interesting one.

To review then, “hashish” was the word of choice for intoxicant cannabis pretty much nationwide in the 1910s, while “marihuana” was quickly gaining ground overall, but was still only really well known in a few Southwestern hotspots.

So what kinds of stories were these?

Hashish Stories

In the case of hashish, a large percentage of stories were fiction. Of the 652 articles where hashish was the primary term used for cannabis, 27% (179) were fiction. You can see that this was significantly higher than the percentage of fictional stories for any other term:

Hashish was a well-worn orientalist literary device, appearing in the The Count of Montecristo, and many other works since the middle nineteenth century hashish vogue among Romantic authors like Balzac, Dumas, and Baudelaire. The latter was of course responsible for the deeply influential phrase, “artificial paradises” that appeared again and again in the sources in reference to hashish intoxication. As an article in the Omaha Daily Bee put it in 1910. “Anyone who has read Dumas’ Monte Cristo knows the effect of Hashish. The book is fiction, but the picture is real.”[3] Similarly, in 1910 various newspapers published excerpts from Her Smile, a short story by Edward C. Bingham. There the protagonist explains about a young widow at the center of the story:

Mrs. Alvord was a witch. I was a bachelor and had never been in the slightest degree affected by any woman. Yet here within half an hour a woman had infatuated me. When she had left me with such a smile as she might have given me had I been her attorney instead of Jorbert’s, and the door closing shut her from my view, it seemed as if I had taken hashish or some other drug to set my brain waltzing through paradise.[4]

Notice how this trope needed no further explanation in 1910. Hashish was already the well-known drug of “Paradise.” Similarly, in 1914 the Albuquerque Evening Herald reported on “New Books at the Public Library”:

IT HAPPENED IN EGYPT by Williamson—it is a story of Egypt and tells how Monny Gilder saw it Egyptian fashion. Monny was rich, attractive and willful. So when she decided to see a hashish den, there she went willy-nilly; when she decided to recapture an American girl from her Egyptian husband, not all the Mohammedans of Laxon could prevent her. How Fenton finally wins Monny, and Biddy finds her first love again are the romances of the story, for which the beauties and mysteries of the desert are in the background.[5]

Or in the “Iltar’s Marriage Rug,” by Orna Davis:

On the third evening Ali Khan drew from his pocket a leathern pouch.

“Tomorrow morning, please Allah, I must leave thee and return to my own people. A true believer has presented me with this packet of purest hashish. Wilt though deign to smoke with me, O descendent of the prophet, that my poor story of the forty parrots may seem more worthy to thee?”

Haji Kassen’s face broke into a hundred wrinkles of delight. He had used the drug on many occasions and he knew its power of transporting the individual to the seventh paradise of Allah.

As he smoked the room grew into a palace, its walls hung with marvelous colors. Ali Khan’s voice swelled into a chorus of melodious voices. Iltar, rising to replenish the fire, became a dozen beautiful maidens whirling in a dance about him.”[6]

Or in the serialized story, “The Pool of Flame,” by Louis Joseph Vance, which was published in newspapers across the country.[7] Though this one reproduced a real slice of reality by depicting the smuggling of hashish from the Greek islands into Egypt, a scenario recently documented by Haggai Ram in his terrific book Intoxicating Zion. But in general, these were fictional stories depicting the familiar tropes of orientalism—dreams of Paradise, sensual pleasures, fanaticism, irrationality, and so forth. The familiarity with which hashish was described in these stories demonstrates that while intoxicant cannabis was a relatively minor presence in the newspapers of the day in comparison to other drugs, its reputation as a foreign, quintessentially “Oriental” drug was already well established by the second decade of the twentieth century.

But there were plenty of non-fiction stories as well. These took various forms. In the case of “Effects of Drugs,” published in the Perth Amboy Evening News, the newspaper just offered some comments on drug effects apparently apropos of nothing.

Persons employed in Indian rubber factories sometimes inhale bisulphide of carbon and suffer from frightful dreams of being murdered or of falling over precipices. Opium stimulates imagination; alcohol in excess excites dread and suspicion; hasheesh, from which the word assassin was derived, produces homicidal mania. These drugs have a distinct effect upon the moral sense. Sometimes, as from alcohol, a course and stupid brutality is stimulated, or, as from morphia, a gloomy and morose temper, or, as from cocaine, while the manner remains gentle, the victim develops thieving and lying habits.[8]

This story was reprinted a dozen times in newspapers around the country. Similar was “W.C.T.U. Notes,” printed in the Santa Fe New Mexican on April 1, 1911.

A sensitive, excitable nature characterizes all animal life, and man, with an animal basis, is exceedingly susceptible to excitement, which must come either through the physical being, the mental nature, or the moral and spiritual capabilities; and the downward tendency of human nature is to seek excitement in the subcellar of its being, and the biggest task we have is to get folks to move upstairs.

For people of every clime and age have found methods of gratifying this lower propensity with intoxicants. The Hindu chews his betel nut and pepperwort; the Indian of the Andes his quid of coca leaves, reveling in its narcotic delirium, or the thorn apple, under whose intoxication he imagines that he communes with the spirits of his progenitors….The negroes of the south are being victimized by cocaine. Tea, when extensively used with strong decoctions, has been known to produce positive intoxication, while among savage tribes, cruder compounds had stimulating properties, resembling alcohol. Besides these the Turks, forbidden by the Koran to drink wine, have long been accustomed to hasheesh, a drug extracted from the hemp of India; but opium, alcohol and tobacco are more extensively used than any other drugs.

From mescal bean to hasheesh, we have through hops, alcohol, opium and tobacco, a sort of graduated scale of intoxicants which stimulate in small doses and narcotize in larger.[9]

Other stories might report on specific incidents in the U.S. or abroad, as in the case of some English officers who were arrested for smuggling hashish into Egypt.[10] There were also long-form stories that described the use of hashish in the Orient. “A great part of the ‘oriental calm,’” one such story claimed, “is due... to the habitual use of opium or cannabis.”[11] There were also often very brief references to hashish that offered no further explanation, something that indicates just how established and taken for granted the discourse on hashish already was. On May 22, 1910, for example, Washington, D.C.’s Evening Star metaphorically referred to fantasies and lies simply as “hasheesh stories.”[12]

I purposely pulled all of these examples from 1910 just to show that these discourses were already established by then, but there were also plenty of similar examples throughout the rest of the decade. As far as I can tell, nothing really significant changed over these years in the shape of the discourse related to hashish.

Marihuana Stories

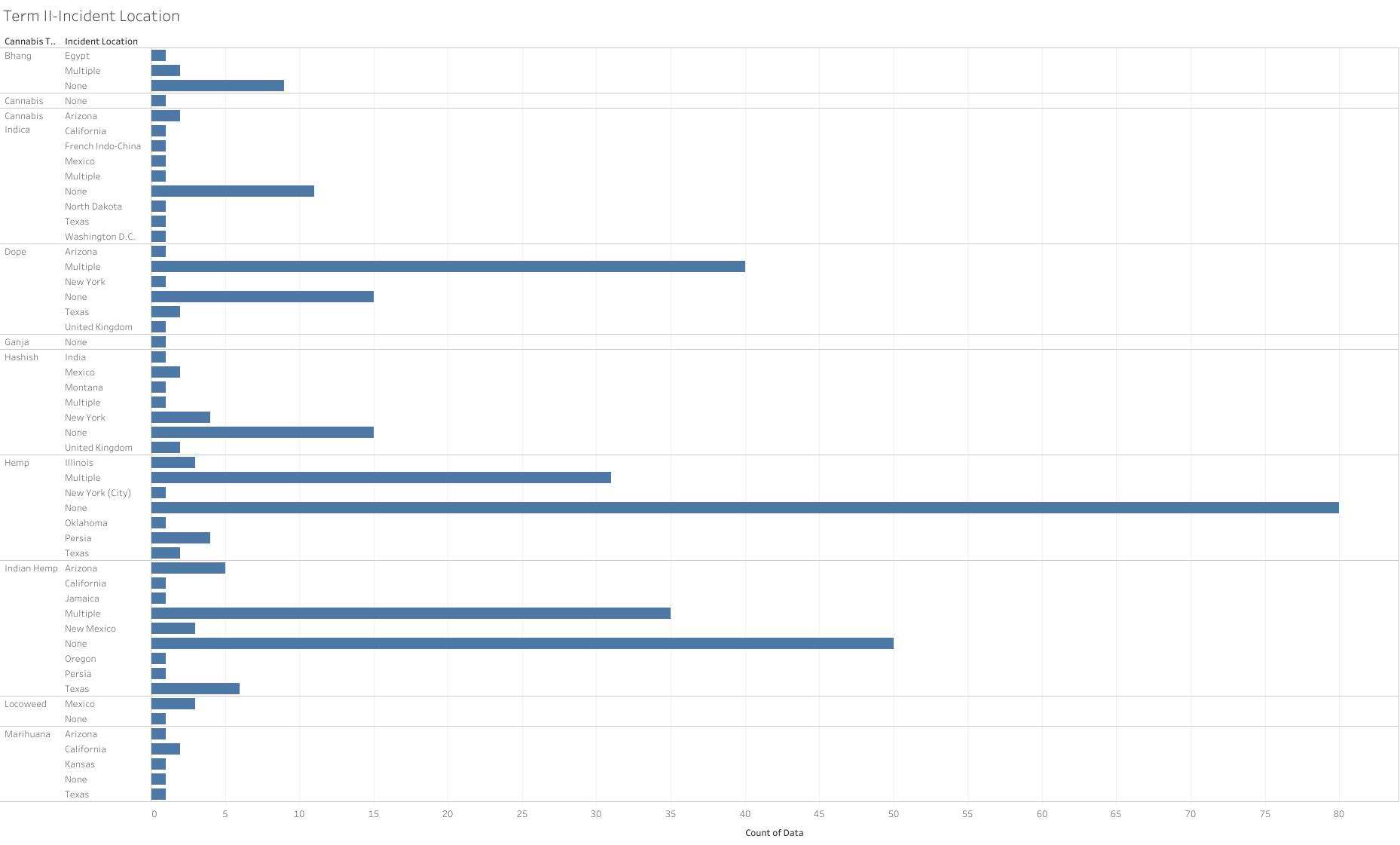

Beyond the geographic concentration mentioned above, perhaps the biggest difference between stories using the word “hashish” versus those using “marihuana” was that the latter much more commonly reported actual news, or what we called “incidents” related to the drug. We defined an “incident” as an actual event involving the use of the drug or attempts at its suppression. Thus arrests, reports of use, or legislation constituted “incidents,” as opposed to simple reports of the existence of the drug as in so many of the hashish stories above. Here is a look at the recorded “incidents” by term and state or country.[13]

“Incidents” were more likely in stories using the word “marihuana” in comparison to hashish, though once again such incidents were relatively isolated geographically, being concentrated in Texas, Arizona, and Mexico. When hashish was used as a primary term, 150 of the 652 total stories, or 23%, involved an “incident.” With “marihuana” it was 210 out of 275, or 75%. We’ll dig into the nature of these later on, but it does once again speak to that curiosity of cannabis history in the U.S. that after decades of availability in this country in pharmacies, it was apparently only in the early twentieth century that recreational cannabis use really seemed to catch on, and this in relation to the drug as it was becoming known as “marihuana.” I suspect this was due to a combination of the Mexican-style “marijuana” cigarette becoming popular, which made dose control much easier, and the much-remarked upon phenomenon of “substitution,” that is, people beginning to use cannabis because alcohol, cocaine, and the opiates were being prohibited. A number of sources from the period credit the latter with the growth in marijuana use.[14] The former is just a hypothesis.

For the moment, let’s just look at the general outline of stories that included marijuana.

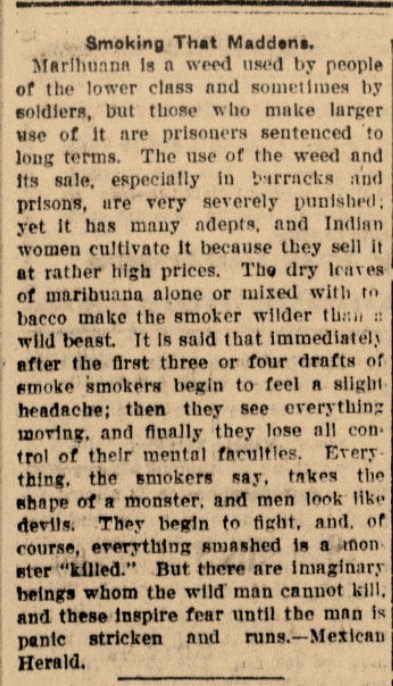

First, there was a genre that I detailed in the ninth chapter of my book, which were stories directly from the press in Mexico that made their way into the U.S. wire service. This process began in the 1890s and usually involved The Mexican Herald as the main conduit, an English-language newspaper in Mexico City that had the AP franchise for that city. Thus its stories were regularly picked up by other newspapers and distributed around the U.S. Typical of this was “Smoking that Maddens,” which appeared in Cairo, IL in October 1910 and then at least a dozen papers after that.

The dry leaves of marihuana alone or mixed with tobacco make the smoker wilder than a wild beast. It is said that immediately after the first three or four drafts of smoke smokers begin to feel a slight headache; then they see everything moving, and finally they lose all control of their mental faculties. Everything, the smokers say, takes the shape of a monster, and men look like devils. They begin to fight, and, of course, everything smashed is a monster “killed.” But there are imaginary beings whom the wild man cannot kill, and these inspire fear until the man is panic stricken and runs.[15]

There were also stories along the border, especially in El Paso, Texas, of drug activity on the Mexican side. For example, a 1912 story in El Paso demonstrates the intermixture of the opium, hashish, and Mexican marijuana discourses:

Most of this piece dealt with the use of opium and concern about the “better families” of El Paso becoming involved. It claimed that of El Paso’s 200 “dope fiends,” about one-third were from “decent homes,” meaning “clerks, professional men, wives and other respectable environments.” But the article also dealt with marijuana which was depicted as a threat confined, at least for the moment, to the Mexican side of the border: “In Juarez may be found a drug fiend of another type—different from the drug victims of any other place—the Marihuana victim. Of all the drugs, Marihuana, Cannabis Indica, or commonly called Indian hemp, experts declare to be the most deadly in its effects. It is so deadly the white man turns it down, but the lower class of Mexicans eagerly seek it.”[16] And so forth. This was basically the typical Mexican discourse on marihuana as reported in the “Smoking that Maddens” story above, but of course in this case it was a nearby threat, just across the border.

Of the same genre but more significant was a story that appeared in the same paper concerning another incident in Juárez, this one involving two Americans who, on New Year’s Day 1913, were attacked by a marijuana user.[17] This one set off a series of efforts to get marijuana prohibited in El Paso, leading to the city’s prohibitory ordinance of 1915, which I wrote about briefly in my SHAD piece and amateur historian Bob Chessey has covered more extensively.

Gradually there were more stories about “marihuana” on the U.S. side. Some of the earliest during our period involved prisoners (much like similar stories in Mexico), such as a report from Arizona in April 1912, or one in El Paso in July 1913. In the latter, marijuana was described as a drug that makes men “see blue monkeys.”[18] Then there were many stories, mainly in El Paso and Phoenix, about the arrest of marijuana users and sellers. Sometimes these were actual news stories, though often they were just short references in police blotters.[19] There were also stories in other parts of the country that described the marijuana situation along the U.S. side of the border. These were often reprinted several or dozens of times in various states.[20]

As with many offhand, casual references to “hashish” that clearly presumed prior knowledge of the drug, there were similar references to “marihuana,” though these were most often in the Spanish language press, such as when La Prensa in San Antonio regularly referred to the usurping Mexican president Victoriano Huerta as “el marihuano” or his followers as “marihuanos.” As I note in my book, this was the origin of the marijuana reference in the famous song “La Cucaracha,” about the cockroach that doesn’t have enough marijuana to smoke. The “cockroach” in the story was Huerta, not the followers of Pancho Villa who were fighting Huerta as various sources have erroneously suggested.[21] There were also advertisements in the Spanish-language press for medicinal goods that often included the word marijuana but not much else.[22]

Sometimes stories would combine terms, of course. A 1917 story in the Abuquerque Morning Journal reported that “hashish” had made an appearance at the local military base, with “probably as many as 100 soldiers” smoking the drug there, a situation that was much lamented by Lieutenant Thomas Noe. “The Lieutenant believed that hashish was introduced at Camp Funston by soldiers who served on the Mexican border and became addicts there. He gained experience with users of the drug when he was provost marshal at Columbus, N.M., and quickly detected its appearance at Camp Funston….Hashish is a powerful narcotic and large doses are fatal. It is known along the Mexican border under the Spanish name of mariguana. In that region addicts mix it with tobacco, roll the mixture into cigarettes and smoke it.”[23] Concern about soldiers using the drug apparently inspired a new ordinance in Albuquerque prohibiting the drug.[24]

Here we see how the longstanding hashish discourse was beginning to mix with the marijuana discourse more recently arrived from Mexico. This should perhaps hardly be surprising given that this was ultimately the same substance. But surely it also had to do with the supposed “oriental” nature of both peoples in Western discourse. Consider a piece that appeared in May of 1914 in New York City’s The Sun and quoted heavily from Hamilton Fyfe’s book, The Real Mexico:

To Europeans (of course I include Americans in that term) the Mexican mind is a mystery; just as much a mystery as the Chinese mind. All Asiatics are a puzzle to us. They do not reason as we do. Their minds are divided into compartments it appears. Whether the Indians who peopled Mexico before the Spaniards came were descended from Asiatic immigrants or whether Asia was invaded in the twilight of the world by races from the American continent, no one can yet tell. But clearly the Mexicans are Asiatic in the sense that they and the peoples of Asia had common ancestry….Nor is it only among the lower class that Oriental features are common. General Huerta himself, a pure Indian, might, if he were dressed in Madarin robes, be mistaken for a genuine wearer of the Yellow Jacket.[25]

Here marijuana, along with strong drink, was described as the curse of “the Mexican.”

Other Terms

Meanwhile, “cannabis indica” was overwhelmingly associated with medicinal preparations of the drug, whether in simple corn-cure recipes, or in warnings about patent medicines that contained dangerous narcotics, one of which was often cannabis.[26] Contrary to the notion that cannabis was merely seen as a useful medicine, these stories make clear what Adam Rathge has demonstrated in his dissertation: that cannabis was seen as both potentially useful, and potentially dangerous.

“Indian hemp” on the other hand was a mixture of the above discourses. Like “cannabis indica,” some stories referred to its inclusion in medicines, and often this suggested the danger of using it as in the case of a child who was supposedly euthanized using opium and Indian hemp.[27] Often it was used as a synonym for drug cannabis whether the first word used was hashish or ganja.[28] One especially noteworthy article of this kind was titled “Ganjah Smoking” and suggested that it had been Hindus who had introduced “ganjah” or “Indian hemp” to California.[29] This may be the origin of the famously cryptic comments by Henry Finger in California, first cited by Dale Gieringer, that “Hindoos” had introduced the practice of cannabis smoking to that state (see note 4 here). Sometimes “Indian hemp” was mentioned in orientalist fiction much like hashish.[30] And sometimes it was mentioned as a veterinary medicine.[31] In short, “Indian hemp” was a familiar synonym for drug cannabis that could appear in the whole gamut of cannabis stories available in the press of the day.

“Hemp” on its own usually just appeared as a descriptor, as in marihuana is “Mexican hemp,” or “cannabis indica (a gum resin produced by hemp, narcotic and intoxicating).”[32] Or it could refer to cannabis fiber. We tried to avoid fiber stories in our search, but sometimes they turned up anyway.[33] At other times, stories combined all of these attributes, as in, “The hemp tree is one of the most versatile plants in the world. From it comes, besides rope and wrapping paper, the drug hashish, called by its devotees ‘the joyous,’ obtained by boiling the leaves and flowers with fresh butter.”[34]

What about “incidents” and these other terms? Above we’ve already looked at Term I and “incident location.” Below are Terms II, Terms III, and a chart with all of the incidents tallied:

Overall we see that, among the terms that have a significant sample size, “marihuana” was much more likely to be connected to actual incidents than anything other than the word “dope,” though some of the other terms approached 50% of their references being associated with “incidents.”

In sum, by the 1910s cannabis had a well established reputation as an intoxicant, with heavy orientalist connotations. Even as the Mexican “marihuana” discourse began to enter the picture, it seamlessly melded with those existing orientalist stereotypes. Clearly the drug did not need to be exoticized with the name “marihuana” in order to raise concerns about it. It was already very much understood as an exotic, quintessentially “Oriental” drug. And, with respect to the rest of the theory about William Randolph Hearst and the supposed nomenclature conspiracy, Hearst papers were a decided minority of the stories on drug cannabis and especially those using the word “marihuana” in the Chronicling America corpus for these years. Below is a list of the Hearst newspapers available in the Chronicling America collection for the years under examination. I’ve listed them along with their publication dates, how many cannabis stories they included, and the nomenclature used in those stories.

In short, there has never been any evidence of a conspiracy to use the word “marihuana” to demonize cannabis, and our evidence here demonstrates pretty clearly that no such conspiracy existed in the 1910s, nor was one necessary. Though here we’ve merely scratched the surface of the discourse on cannabis.

In our the next post, we’ll consider the effects that were attributed to drug cannabis and how these might have varied based on geography and nomenclature.