Cannabis Historiography (is a bit of a mess)

[Image: Wikimedia Commons]

Background

Cannabis was prohibited on the federal level in the United States in 1937, though there were some earlier federal laws that restricted its availability and circulation. The 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act included labeling requirements for products that contained cannabis, and a 1915 amendment to that same law only allowed for the importation of “medicinal” cannabis to the United States. But it was the “Marihuana Tax Act” of 1937 that essentially outlawed recreational cannabis throughout the U.S. for the first time (I say “essentially” because it was still technically legal to pay the enormous transfer tax, roughly $2000 per ounce in today’s dollars, and acquire drug cannabis).

Yet laws requiring a prescription to buy cannabis had begun to appear in the late nineteenth century and outright prohibitions date to the 1910s, beginning with Massachusetts’ statute of 1911, followed by various other states (1913: Maine, Wyoming, Indiana, California; 1915: Vermont and Utah; 1917: Colorado and Nevada; 1918: Rhode Island; 1919: Texas). By the time the Marihuana Tax Act was passed, every state already had legislation that at least required a prescription to buy drug cannabis. [1]

Research on all of this began more than half a century ago but there still remains a lot of confusion about this history in the literature. In part, this just reflects a lot of contradictory and spotty evidence. But in other ways it’s a symptom of some larger problems with the way history is written, especially on a topic like this one that has so much contemporary political salience. Thus, before we get into the more specific details of marijuana’s history in the United States, I’d like to consider some of these more general problems that afflict this particular literature or “historiography.”

What is Historiography?

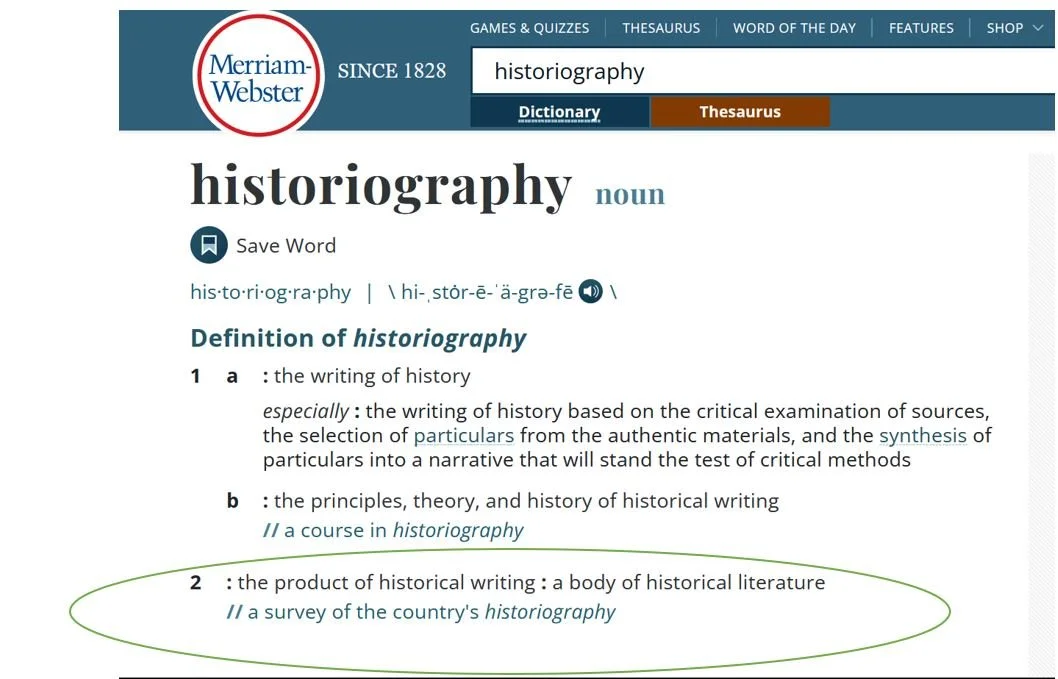

While “historiography” can mean “the writing of history,” or “the principles, theory, and history of historical writing,” nowadays historians more often use the term to refer to “the product of historical writing,” or “a body of historical literature.” In other words, the collected works written, whether in book or essay form, on a particular topic in history. This is sometimes also referred to as the “historical literature.” Thus, for example, there is a historiography on the origins of the First World War, another on the origins of the Mexican Revolution, another on the decision to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima, another on the everyday lives of workers during the industrial revolution, and so forth. And, of course, there is also one on the origins of marijuana prohibition in the United States.

Historians develop knowledge through a systematic process whereby new research is in constant dialogue with established knowledge. That established knowledge is what we call “the historiography” or “historical literature.” Now “established” is not the perfect word here because it denotes something a little more permanent than most historiographies can hope to become. While wordier, it’s probably more accurate to describe the reigning historiography as the “currently accepted” knowledge rather than “established.” There are a few reasons for this. First, history is incredibly complex and messy. Most events are, as sociologists like to say, “over-determined,” meaning that they have more than one cause. So historians can debate endlessly over which of those causes is most important. Did the First World War begin because Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated? Or did it begin because of imperial rivalries that had reached a breaking point? Clearly both played a role, but which was paramount?

Opinions of course vary significantly on that question, as they do with so many others in history, ultimately coming down to philosophical differences between the interpreters. Thus sometimes we crudely classify historians into two camps: “Lumpers,” and “Splitters.” The splitters tend to prioritize the actions of individuals and key events (e.g., Franz Ferdinand’s assassination). Lumpers tend to prioritize longer-term developments like imperial rivalries, economic systems, demographic shifts, and so forth. We all have our tendencies toward lumping or splitting, though most of us do a little of both. But there’s a lot of room for variation, thus two equally informed, rational, and honest historians can come to very different conclusions about the exact same evidence. That begins to explain why knowledge rarely reaches the difficult threshold of being “established.”

But there are other reasons too. Historians interested in, say, the origins of the First World War will benefit from lots of available evidence because the decision to go to war rested in the hands of powerful statesmen working in large institutions (i.e. governments) that preserved a lot of material (correspondence, memos, meeting minutes, etc.) related to those decisions. But there are all sorts of questions that don’t benefit from such a rich paper trail. For example, at the beginning of the twentieth century in Mexico, only about 14% of the population was literate. As we try to understand, say, the origins of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, it’s very difficult to pinpoint why the average Mexican chose to rise up in revolt or not. Historians have done their best to explain it, but there will continue to be debates because there simply is not enough evidence to reach any firm conclusions. There are lots of important historical questions, including the origins of marijuana prohibition in the U.S., for which there are major evidentiary gaps. And debates over scanty evidence are even more likely to reveal philosophical differences between lumpers, splitters, and any number of other ideological camps.

There are two ways to deal with all of this uncertainty when writing about history. One is to constantly offer caveats and disclaimers about the state of our knowledge. For example, one might write something like this: “While we can’t be certain given the gaps in the evidence, the most reasonable explanation appears to be that…” This is the honest, scholarly approach. But, admittedly, such an approach does not produce the most appealing and engaging prose. Readers—and thus publishers—generally prefer a more authoritative presentation of the story and related facts. This is clearly more stylistically appealing and probably more psychologically satisfying as well because readers can feel like they are really learning something concrete. There’s surely an ideological element as well since it will be especially satisfying if the authoritative account reinforces one’s own political biases! But such accounts often misrepresent how firm the evidence actually is.

Now, authoritative accounts, even when they gloss over some of the uncertainty in the historiography, are not necessarily a bad thing as long as everyone understands that they are surely glossing over a lot of uncertainty. But I think it’s safe to say that most people, when they read such authoritative treatments, are not aware of just how much uncertainty has been glossed over. And that, I think, is problematic.

This is why professional historians tend to err on the side of clunky, caveat-filled narratives. It’s also why many of us deride the best sellers as “pop” history (while quietly envying their accompanying royalties). But, as a result of our approach, most professional historians don’t sell many books and thus don’t have that much of an immediate impact on the broader conversation about history. That is also a problem. One would hope that today’s important political or cultural debates would be informed by the most careful, nuanced, and honest interpretations of the past.

Of course professional historians are not the only people who write about history. This is especially the case with a subject like marijuana which has so much contemporary political salience. Indeed, very little of marijuana’s history in the U.S. has been researched and written about by scholars with a PhD in history. Among academic works, scholars from the more present-oriented fields of sociology and the law have been the most prominent contributors to this literature. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, but it speaks to how much contemporary concerns have driven research in this field. Meanwhile, there’s also an enormous popular literature written by journalists, activists, and people from any number of other backgrounds. These popular accounts draw on some of the scholarly work but rarely in the kind of systematic way that scholars do. Add in the arrival of the internet, where everyone is free to “publish” authoritative statements about “the facts,” and you have a potential mess on your hands. And a mess is indeed what we have when it comes to the historiography on marijuana’s prohibition in the United States.

Anatomy of a Historiographic Mess

This mess has a few key traits:

First, there are a number of arguments that are widely treated as “fact” though they have never been supported by much, or in some cases, any evidence at all. As I detail in a 2018 piece in the Social History of Alcohol and Drugs that I will refer to repeatedly in these posts, even some of the best of the early scholarly literature on marijuana’s prohibition at the state level in the United States had some huge evidentiary holes that have simply been overlooked by countless subsequent publications. We can really only speculate as to why. I suspect that perhaps the findings and arguments in these works just seemed plausible based on the situation in the present (I elaborate a bit on this in the next post). Indeed, historians are trained to always beware of interpreting the past through the lens of the present, because the present can badly distort our view of the past. But it might also have simply been confirmation bias. It’s probably a bit of both.

A second trait of this historiographic mess is that even when there are advances in the scholarship that either invalidate older arguments or raise considerable doubts about them, they are often ignored by new publications. Way back in 1983, for example, the sociologist Jerome Himmelstein analyzed the discourse surrounding the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act in 1937, and noted that, contrary to the common claim that that law was justified through constant racist references to minority cannabis users, in truth the main justification at the time of the legislation was the notion that marijuana use was spreading to children. But Himmelstein’s findings, though they have never been refuted, were for decades almost completely ignored. The legal scholar George Fisher has recently reiterated Himmelstein’s points, but the fact that he has had to do so is quite telling.

A third and final trait of this historiographic mess is that it continues to be deeply influenced by contemporary political concerns. This helps explain why one of the most influential book on marijuana’s history in the U.S., at least in terms of popular discourse, has been Jack Herer’s 1985 conspiracy tract, Hemp and the Marijuana Conspiracy: The Emperor Wears No Clothes, despite it being among the least scholarly of all the contributions to the literature, and despite its obvious political motivations.

If you’d like to read a more thorough critique of some elements of the existing historiography, I recommend you read my 2018 article that you can download for free here. For now, I’d like to conclude this brief overview with one especially pertinent example of how a historical account based on scant evidence, but written in an authoritative style, can provide the seeds for significant distortions in our understanding, especially when those seeds are subsequently nurtured by people who have little regard for the actual facts.

Jack Herer and the Hemp Conspiracy

Surely the most influential scholarly work on marijuana’s history in the U.S. continues to be The Marihuana Conviction, first published in 1974 by the law professors Richard Bonnie and Charles Whitebread. This work, while deeply researched and seriously written, has proven a breeding ground for a number of key mythologies in the literature. This is, I think, in part due to the authoritative tone of much of their writing. Though there were major gaps in the evidence, the two lawyers, perhaps unsurprisingly given their profession, consistently made their case with the confidence and forcefulness of litigators before a jury. But few readers seem to have realized just how limited some of the evidence for their claims actually was.

The example I’d like to highlight here actually involves one of the more measured portions of their argument. At the center is the role that the Hearst newspaper chain supposedly played in igniting a moral panic about marijuana in the 1930s. While discussing efforts to get marijuana banned through the passage of a “Uniform State Narcotics Act” in the early part of that decade, Bonnie and Whitebread note that the Hearst newspapers were “among the most effective proponents” of that process. To back this claim, they drew on a very suggestive quote from William C. Woodward, legal counsel for the American Medical Association, who noted that “the support of the Hearst papers should contribute materially toward procuring enactment of legislation.” Bonnie and Whitebread then went on to cite several articles in Hearst newspapers in support of that legislation. [2]

Now, this is quite interesting evidence, but hardly conclusive on its own, particularly given the ubiquity of negative stories about marijuana during these years. Indeed, Bonnie and Whitebread acknowledged as much themselves by noting in the main text that “The Hearst chain was not alone,” in promoting the law’s passage, and then citing several examples from non-Hearst sources. Then, in the relevant endnote, they write: “Someone should do a study on the activity of the Hearst papers on the drug front during the formative years.” [3] In other words, no one had yet looked at this systematically to find out if the Hearst chain was actually any more prohibitionist than any other newspaper chain. As far as I know, that work is still yet to be done despite the ubiquity of claims that the Hearst chain was crucial in all of this. The quote from Woodward was certainly suggestive, and the chain apparently was commended in 1937 by a law enforcement organization “for pioneering the national fight against dope” (the authors cite a Hearst newspaper for this information), but as Bonnie and Whitebread themselves recognized, there were plenty of other sources publishing disturbing stories about the “marijuana menace” at the time. Thus they merely wrote that the Hearst press was “among the most effective proponents,” and that was a reasonable interpretation of the evidence, especially if you read the relevant endnotes.

But the activist Jack Herer ran with the idea that Hearst was a key player in this, despite the skeletal evidence, and invented, basically out of whole cloth, some new elements of the story, claiming that Hearst, who was supposedly angry at Mexico and Mexicans for confiscating large tracts of his property during the Mexican Revolution, manufactured the crisis by popularizing the term “marihuana.” Here’s Herer:

Hearst, through pervasive and repetitive use, pounded the obscure Mexican slang word ‘marijuana’ into the English-speaking American consciousness. ‘Hemp’ was discarded. ‘Cannabis,’ the scientific term, was ignored or buried.

The actual Spanish word for hemp is ‘cáñamo.’ But using a Mexican Sonoran colloquialism-- marijuana, often Americanized as ‘marihuana’-- guaranteed that no one would realize the world’s chief natural medicine and premier industrial resource had been outflanked, outlawed and pushed out of the language. [4]

Like so much in Herer’s book, this is both wildly inaccurate and apparently based on no evidence whatsoever. “Marihuana” is the most common Mexican spelling of the word (it’s the spelling with a ‘j’ that is the Americanized form), it was hardly obscure in Mexico as it had been the most common word for intoxicant cannabis in that country for nearly a century, there is not to my knowledge any evidence that the word derives from the state of Sonora, and, finally, and most importantly, there is zero evidence that the Hearst chain or anyone else made a conscious effort to use the word “marihuana” in order to smear the drug. [5] Later, Herer argues that this was an absolutely key element in the demonization and prohibition of cannabis:

What socio-political force would be strong enough to turn Americans against something as innocent as a plant—let alone one which everyone had interest in using to improve their own lives?

Earlier, you read how the first federal anti-marijuana laws (1937) came about because of William Randolph Hearst’s lies, yellow journalism and racist newspaper articles and ravings, which from then on were cited in Congressional testimony by Harry Anslinger as facts.

But what started Hearst on the marijuana and racist scare stories? What intelligence or ignorance, for which we will punish fellow Americans to the tune of 12 million years in jail in just the last 50 years (390,000 arrested in 1990 alone for marijuana)—brought this about?

The first step was to introduce the element of fear of the unknown by using a word that no one had ever heard of before: “marijuana.”

The next step was to keep maneuverings hidden from the doctors and hemp industries who would have defended hemp by holding most of the hearings on prohibition in secret.

And, finally, to stir up primal emotions and tap right into an existing pool of hatred that was already poisoning society: racism. [6]

If you’ve ever heard that the word “marijuana” is racist, these are the origins of that idea—in a baseless conspiracy theory. I’m not aware of a shred of evidence to back the claim that this word was used purposely by the Hearst chain, Anslinger, or anyone else to demonize the drug or its users. As we will see here, the word was coming into the American lexicon quite organically by the 1910s. Bonnie and Whitebread merely argued that Hearst papers “were among the most effective proponents” of the Uniform State Narcotics Act. Herer made up the details about the word “marijuana” apparently from whole cloth.

Yet this idea has become embedded in the public consciousness and, it seems, especially in the cannabis industry. For example, NewsBank, a company that touts itself as “a premiere provider of the world's largest repository of reliable information,” has recently launched a “Cannabis NewsHub” to respond to the cannabis industry’s desire for “reliable, comprehensive coverage specific to the industry and the topics most important to them.” There, under “History,” one finds quick links to sub-themes that demonstrate the obvious influence of Herer, especially the sections titled, “Racism Against Mexicans Spurs Cannabis Fears,” and “Hemp Competition with Paper, Nylon Industries.” Click on the “Racism” link, and you’ll find dozens of stories that repeat the major themes from Herer’s conspiracy theory, as in this March 14, 2011 op/ed in the Santa Fe New Mexican:

Hispanics in New Mexico should be up in arms opposing federal marijuana laws because those laws are a constant reminder of the history of prejudice against our people in this country….A major motivator for the federal government's weed laws is prejudice against Hispanics. Almost a century ago, William Hearst, a vehemently anti-Mexican Californian, launched a nationwide campaign through his Hearst newspaper chain to turn the population against Hispanics….As part of his overall campaign to depict Mexicans as a threat to America, California and the Southwest, Hearst agitated nationally for federal marijuana laws. In the early 20th century, most Americans knew nothing about weed, while this cheap intoxicant was commonly used by poor Hispanics and blacks. Hearst, who had lost hundreds of thousands of [acres of] newspaper pulp timberland in Mexico to government confiscation, spent his revenge on poor Mexicans in the U.S. by unleashing his powerful nationwide newspaper chain on a decades-long campaign to slur the Hispanic people in every way possible….How can New Mexico Hispanics sit by passively with this historical scar of racism exposed to us every single day? [7]

in short, the notion that the word “marijuana” was purposely used to smear cannabis in the U.S. has become entrenched in the public discourse, though there is literally no evidence that this was actually the case. Now various states are passing legislation to erase the word “marijuana” from the official record.

Indeed, perhaps the most interesting part of all of this is how much influence these ideas have had on the legislative process in the United States, whether in helping to galvanize support for marijuana law reform (surely a good thing), or in leading state legislatures to strike marijuana from the official record (probably a relatively unimportant thing). Here we see that what actually happened is sometimes less important than what we think happened.

Whatever the case, there is certainly a lot of misinformation out there. Here we’ll do our best to sort fact from fiction, and we’ll try to always be clear about what we know, what we don’t, and everything in between.