Cannabis Effects as Reported in the Press 1910-1919

In 1971, Keith Stroup of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, or NORML, began showing the film Reefer Madness at rallies for his organization. The film famously depicts madness, violence, and suicide as resulting from the use of cannabis. By showing the film, Stroup clearly meant to suggest that federal marijuana prohibition had been enacted in an atmosphere of hysteria about this drug’s effects.

Stroup’s gambit was an extraordinarily successful one and the phrase “reefer madness” came to mean several things at once. It could refer to the ideas (madness, violence, etc.) represented in the film, but it also began to be used as a critique of marijuana prohibition which itself was characterized as a kind of irrational “madness.” More problematically, the phrase, and the idea that prohibition was based on nothing more than a series of utterly ludicrous ideas about the drug, helped to discredit almost any warnings about the harms of marijuana, even legitimate ones, as the scholars Wayne Hall and Sarah Yeates have recently pointed out with respect to the very real association between cannabis and mental illness. To be clear, this was not Stroup’s intention. As he put it in 1975, “We have to convince legislators that the risk in smoking grass is a reasonable one. We don’t say that pot is 100 percent safe, no drug is harmless.” But many others ran with the notion that all warnings about cannabis were just “reefer madness” nonsense. The origins of these ideas in the United States thus have both considerable historical and present-day significance.

When Stroup was releasing the film, the going explanation was that Harry Anslinger, the Head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, had, if not completely manufactured those frightening cannabis stereotypes, at least played an enormous role in their dissemination. But it soon became clear that they had existed prior to Anslinger’s interest in marijuana prohibition in the mid-1930s. The so-called “Mexican-hypothesis” then emerged to explain their genesis, especially in the Southwest, the argument being that these ideas were fantasies prompted by fear of Mexican immigrants, or were manufactured by racists and xenophobes to demonize those immigrants and their supposed drug of choice (more on this in the next post). We now know that the notion that cannabis produced madness has been common all over the world, and the connection to violence, while not as ubiquitous, was also known elsewhere. Indeed, Mexico was the country that perhaps had the most lopsided view of this drug, with it being overwhelmingly associated with violence and madness there. Those Mexican ideas then began spreading to the U.S. in the 1890s. I cover all of this in my book, (see especially Chapters 1, 4, and 9). Since then, as I’ve already noted, Adam Rathge has demonstrated that cannabis’s reputation as a narcotic closely linked to madness dated to the middle of the nineteenth century in the United States. This is hardly surprising given that cannabis is a psychotomimetic drug (i.e. it can produce symptoms like anxiety, panic, and even hallucinations), and as Hall and Yeates also note in their more recent article, we now know that there is a consistent association between cannabis use and mental illness. Thus the “reefer madness” stereotypes of the 1930s, no matter how absurdly they were portrayed in the film of the same name, aren’t nearly as inexplicable as it seemed to observers in the early 1970s.

However, there are still a lot of questions to be answered about this history. For example, how exactly did the “hashish,” “marihuana,” and “Indian hemp” discourses differ? Were different effects attributed to cannabis depending on which of these words was used? Was there any geographic variation in these discourses? For example, we’ve already seen that the word “marihuana” was more common in the Southwest during the 1910s, but were different effects attributed to the drug in that region as well?

These questions are important because they can help us better understand the process of marijuana prohibition at the local, state, and even federal level. As I’ve already noted, the early twentieth century was a period that saw enormous efforts to restrict access to intoxicants. However, those reformist impulses came into conflict with other interests, whether of the pharmaceutical industry, or doctors who sought to protect their autonomy, or simply those who believed that government should have a very good reason before intruding on the liberty of American citizens. Thus prohibitions had to be well justified and, as a result, ideas about cannabis and its effects were hugely important. Even those who might have been motivated mainly by the identity of the drug’s users were unlikely to simply say, “We have to ban this because Mexicans use it.” They made arguments about what happened when Mexicans or anyone else used it. In short, the development of these discourses is a critical part of marijuana’s history in the United States.

Methodology

To examine how cannabis effects were portrayed in the press, we used two measures. The first, which we termed “Basic Effects,” involved an assessment of the general tenor of an article in relation to the effects of cannabis. These we categorized as positive, negative, or neutral. If an article suggested both a positive and negative interpretation, we labeled it “both.” Often the adjectives used to describe the effects were enough to categorize “positive” versus “negative” (e.g. “The terrible effects of hashish…”). Though in some instances where a specific verdict on those effects wasn’t offered by the article, we thought it reasonable to make some presumptions. For example, if someone was reported as being arrested for the drug, or if a law was passed prohibiting it, then we decided that, for a reader, the connotation regarding its effects would likely have been negative. Similarly, if the word “dope” or “narcotic” was used, this was also presumed to be negative. On the other hand, if it was described as “medicinal,” we considered that an implicitly positive connotation (unless the story specifically cited the dangers of a particular cannabis medication).

Our second measure involved more “Specific Effects,” but before we discuss those in detail, let’s see what the “Basic Effects” looked like.

Cannabis Basic Effects

Out of our 1,225 articles, 1,090 suggested some opinion on the effects of cannabis as an intoxicant. Of these, 64% (696) were negative, 17% (185) neutral; 10% (109) “both”; and 9% (100) positive. Clearly negative stories dominated, though I think it is noteworthy that the number of “neutral” and “positive” stories, if combined, equaled more than a quarter of the total.

Here’s another visualization with the same data:

And another:

So how did all of this break down by the terminology used for cannabis? As you can see below, negative portrayals clearly predominate for all of the terms with the exception of references to “cannabis,” which often appeared in articles about topical remedies for treating corns.

There were also a significant number of “neutral” hashish references, and some positive as well. If we break these down into percentages, of the 652 articles that used “hashish” as the primary term for cannabis, 49% (321) were negative, 26% (169) were neutral, 12% (80) were “both,” 8% (52) were positive, and 5% (30) had no description one way or the other. Thus while negative stories about hashish clearly predominated, there were a significant number stories that were either positive, neutral, or both positive and negative. “Marihuana” stories, on the other hand, were not nearly as balanced. Of the 275 “marihuana” stories, only 3% (8) were positive, 3% neutral (7), and 4% (10) “both,” while a whopping 84% (232) were negative. Of the 89 “Indian hemp” stories, only 4% (4) were positive, 3% (3) neutral, while 61% (54) were negative.

Here's a similar look at the most significant secondary terms (I removed those for which there were only a few articles in order to improve the overall visualization).

“Dope” is the most obviously negative term. Hashish looks similar if perhaps slightly less balanced than when it appeared as a primary term. More interesting is “hemp” which, again, was primarily used to refer to cannabis fiber rather than intoxicant cannabis, yet still appeared in 122 articles as a secondary term. Of these references, 40% (49) were negative, 19% (23) were “both,” 17% (21) were neutral, 17% (21) were positive, and 7% (8) did not judge either way. For “Indian hemp” there were 103 total references, with 54% (56) being negative, 34% (35) “both,” and 12% (12) making no judgement. In short, outside of the medical context, intoxicant cannabis was mostly viewed in a negative light. References to the word “hashish” were the biggest exception, where, at least as a primary term, positive and neutral stories made up 38% of the total. This is quite surprising since “hashish” was, as we’ve seen, a word with obvious and recognized foreign connotations, a quintessentially orientalist symbol, and about as non-Western and “other” a word as you could expect to find during the period.

You might thus be curious if the relative balance in this discourse reflected the relatively high number of fictional stories utilizing the term “hashish.” This may have played some role with respect to “neutral” stories, though not “positive ones” as demonstrated here:

9% of the non-fiction stories were positive versus 4% of the fiction stories, while 20% of the non-fiction stories were neutral versus 42% of the fictional accounts. Still, 46% of fictional stories were negative.

More Specific Effects Attributed to Cannabis

We also tracked what we called “Specific Effects.” As noted in the earlier methodology post, this process required quite a lot of revision and editing because there were a huge number of adjectives used by newspapers to describe cannabis’ effects. At the beginning of our work, we sought to maintain an open mind and simply used the adjectives as presented in the stories. But this resulted in an overwhelming list of terms, many of which were describing essentially the same effect. For example: “cheerfulness,” “delight,” “despair,” and “enchantment” all appeared separately in the sources, but in the end we decided that consolidating them all under the label “altered emotion,” when combined with the “negative,” “positive,” “neutral,” and “both” labels that summarized the general tone of each story, made the most sense. We did the same for adjectives describing various other key effects, in the end boiling things down to a manageable ten:

Addiction

Altered Behavior

Altered Emotion

Altered Perception

Madness

Medicinal

Narcotic/Dope

Physical Health

Vague

Violence

A few of these need some additional explanation. “Addiction,” “madness,” and “violence” are such key terms in the historiography that they deserved their own categories, though obviously “violence” could also fit under the “AltBehavior” label and “madness” could fit under “AltPerception.” Addiction of course was central to concerns about drugs during that (and our current) era and thus also deserved its own category. “Narcotic/Dope” and “Medicinal” were also each very loaded terms, with the former serving to almost instantly condemn a substance, and the latter usually justifying its continued availability. Finally, “vague” was used mostly for stories that implicitly suggested a drug was problematic (e.g., because a law was passed to ban it), but never explained why.

Let’s begin by simply looking at the specific effects alone as they appeared in the corpus:

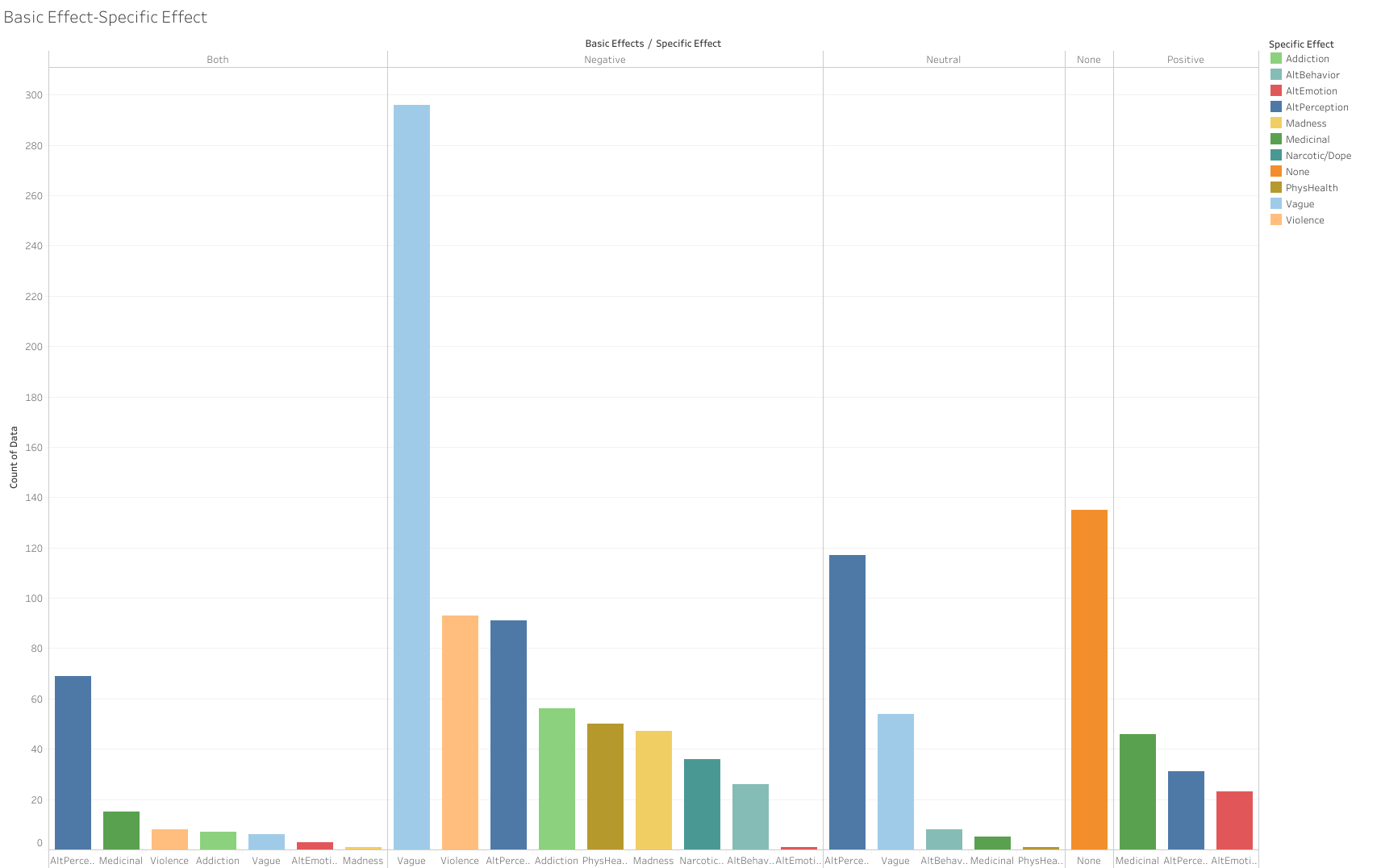

Now let’s examine how each of these specific effects related to the “basic effects” considered above.

A few things stand out here. First, note that when an article was vague about the specific effects involved, the general tenor of the article was most often negative. This appears quite interesting, but, upon reflection, I don’t think it’s too significant. It surely has more to do with our method than anything else. Remember that we considered any story about medicinal cannabis positive by default. In most cases these “positive” references were very vague, but they didn’t count as such under “Specific Effects” because we included a “Medicinal” category there. Thus, while there were quite a lot of “vague” stories with positive connotations, they did not show up that way in our visualizations.

Second, “altered perception” was not only the most commonly cited effect of drug cannabis in general, but it was also the most common specific effects cited no matter what the tenor of the story.

Third, as expected, “medicinal” portrayals were generally positive, but there was room for some negativity in there as well. This was mostly due to concerns about the abuse of cannabis medicines, mainly in the form of consumer exploitation (more on this later).

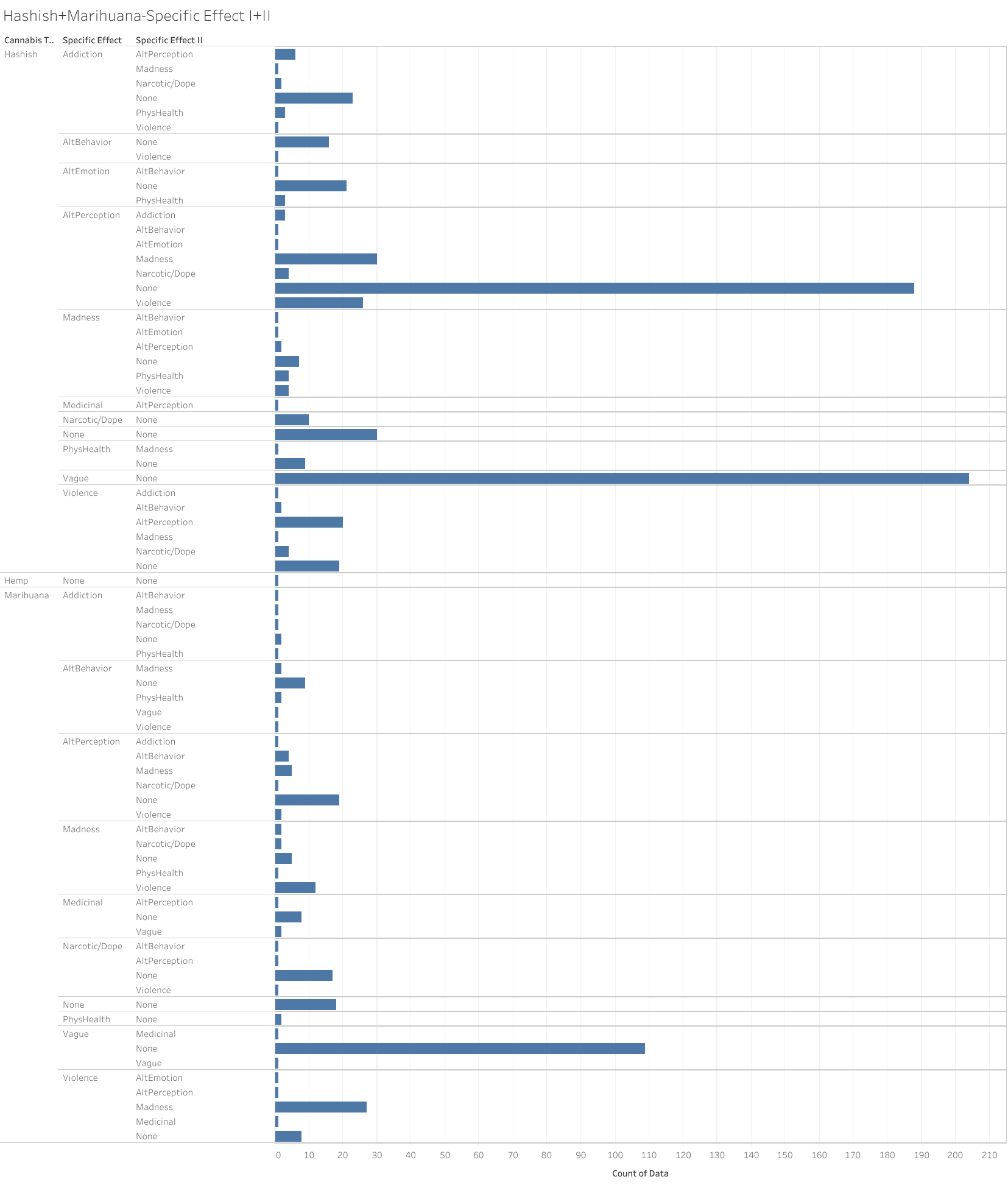

The next visualization looks at the breakdown of articles that had more than one specific effect cited. As with the cannabis terms, we tried to place the most prominent effect first with the secondary second, but this was even less of an exact science than with the cannabis terms, so it’s important not to read too much into the “primary” and “secondary” idea here. Really this is just a look at what effects tended to be cited at the same time (or not).

It’s quite interesting that the most common secondary effects paired with “altered perception,” were madness and violence. This speaks to the danger that was often associated with that altered perception. While, as we’ve seen, altered perception could at times be viewed in a positive light, there was also clearly concern about the potential for negative outcomes to arise from that effect. And this relationship is also seen when “violence” was the primary effect, with “AltPerception” and “madness” coming in as the two most common secondary effects.

When cannabis was associated with violence, it tended to be seen as a result of the user misunderstanding reality and having hallucinations or visions that brought it on. This is somewhat different than the stereotype of the drunkard who simply becomes aggressive as a result of drinking. Indeed, this was the core of the most famous story related to cannabis effects, which was the tale of the medieval “hashishins.” As the Wallowa County Chieftan of Enterprise, Oregon reported in 1910:

There was a terrible secret society in the east which was organized for wholesale and systematic murder. Its members called themselves “hashhasin”—whence, by the way, came our word ‘assassin’—and used to get up courage for their deeds of atrocity by doses of the drug called “hasheesh.” This is obtained from Indian hemp, and it is from the seed vessels that the substance is taken which yields the poison so famed in history and romance. It is a vivid green and when taken produces the most extraordinary visions and hallucinations.[1]

This particular version of the “Hashishin” story was reprinted at least eleven times in various publications around the country, but there were various others that told the same familiar tale first reported by Marco Polo.[2] Most of our references that paired “AltPerception” and “violence” told this story. But of course, as noted above, altered perception is also a fundamental element of “madness,” so we should not underestimate the relationship between those two factors in the data.

In sum, cannabis, both as an intoxicant and as a medicine, was consistently described as being unpredictable in its effects and therefore potentially dangerous. And of course the simple fact that a substance might alter someone’s perception, distorting reality, was enough in the early twentieth century to elicit considerable concern about its use.

Nomenclature and Specific Effects

So how did the reporting on these effects vary in relation to the terminology used for cannabis in the media? Let’s begin simply with primary terms and primary effects:

First, note that vague descriptions were quite prominent, and, as noted above, were actually more prominent than our data even suggests. Second, there’s an obvious distinction between “hashish” and “marihuana” stories. While violence was at times associated with hashish, this was much more the “drug of dreams” and altered perception, whereas marijuana was more likely to be associated first with violence and then altered perception slightly behind. This again surely reflects in part the influence of Mexican discourses. Here is a similar chart I created for my book based on my analysis of Mexican newspapers between 1847 and 1920:

Though we must keep in mind the subjectivity involved in determining which was the “primary” term and which was secondary. Thus let’s also look at secondary terms and the specific effects they were connected with:

There’s nothing really here to change the basic impressions we took from our primary terms except that “hemp,” when linked to intoxicant cannabis, was generally seen as having the same kinds of effects.

We might also wonder if “marihuana’s” outsized number of “violence” and “madness” references versus the “AltPerception” of “hashish” was just an artifact of our decisions regarding primary and secondary effects. But this does not seem to be the case as we can see below with most of hashish “AltPerception” references having no secondary term (though there were some to violence and madness), and most of the primary marijuana “violence” references paired with “madness” and vice versa.

Finally, let’s consider how often each of these of specific effects, when linked to particular terminology, fell on the scale of more “basic effects.”

And for a different perspective, here is the same information but with the basic effects first:

Finally, here is a look at the same variables but as related to our second list of terms.

There aren’t too many surprises here given what we’ve already seen, but a few things are worth noting. First, references to “altered emotion” were overwhelmingly positive. In part this was due to a single short story that was repeated at least eighteen times in newspapers across the country: “The hemp tree is one of the most versatile plants in the world. From it comes, besides rope and wrapping paper, the drug hashish, called by its devotees ‘the joyous,’ obtained by boiling the leaves and flowers with fresh butter…”[3] Though there were two other articles with similarly short references to the positive effects of cannabis, as in the story “Weeds of Value”:

Indian hemp grows wild, and out of it hasheesh, or keef, is made. Keef looks like flakes of chopped straw. It is smoked in a pipe; it is eaten on liver; it is drunk in water. It produces an intense, a delirious happiness; and among Orientals it is almost as highly prized as beer and whiskey with us.[4]

Or in a rather racist piece promoting an upcoming minstrel show: “It will act on the Glooms like Indian hemp or hyoscyamnus (sic) or lactucarium or ‘snow’ acts on a ‘Jingle Bell.’”[5]

Second, there were many “positive” references to altered perception. These were often in fictional accounts of hashish that included lines like, “It seemed as if I had taken hashish or some other drug to set my brain waltzing through paradise,” which described the feelings of infatuation a character felt toward a woman.[6] Or in a story that remarked on the wonders of the telephone and how unbelievable this technology would’ve seemed just a few years before: “It is a fairy tale never equaled by Anderson or Grimm or the delightful hashish dreams preserved in the weird tales of the Orientals…”[7]

While the negative side of “violence” or “madness” or “addiction” is pretty obvious and just what we would expect, negative “altered perception” perhaps deserves some additional explanation. These kinds of stories varied tremendously. For hashish, there were stories that used the drug as a metaphor for irrational political visions, as in, “I find that a stupid dream of a Slav Empire has drugged the best intellects of Kosnovia for half a century. That sort of political hashish must cease to control our actions.”[8] There was a non-fiction story from Paris of two well-borne burglars who were deemed irresponsible for their crimes due to the use of opium and hashish which had altered their perception.[9] There was an obituary for a poet who committed suicide and had written a poem called “hashish” on the effects that the drug has on the imagination.[10] And so forth. For stories referring to “marihuana” there were reports of false courage, and users gaining an irrational sense of their own strength: “The user imagines he is a giant while other persons and objects are dwarfed.”[11] There were also stories that simply described marijuana users being arrested, which in itself made the story “negative,” but then described the altered perception that went along with it: “The weed gives more solace than tobacco and has more kick than the strongest whiskey.”[12] Or it could simply be described as giving false courage to users and thus was seen as very dangerous.[13]

In short, accounts of cannabis intoxication certainly tended toward the negative but there were plenty of positive portrayals, especially of “hashish,” that might have attracted potential users, something we should keep in mind as we consider why intoxicant cannabis seemed to gain in popularity in the early twentieth century.